Sticking closely to the novel by Arthur Conan Doyle, the story sees Holmes and Watson investigating the legend of a deadly supernatural beast that has been haunting the Baskerville family for hundreds of years. After his Charles Baskerville is found dead, his face twisted in horror and giant paw marks near the body, his nephew Henry, the last of the line, inherits the family estate – but has he inherited the family curse? Or is there a more down-to-earth explanation?

Moviegoers in the 1930s had no shortage of detectives to watch, such as The Thin Man, Bulldog Drummond, The Saint, Charlie Chan and Mr Moto. One element of The Hound of the Baskervilles that makes it stand out from these is one that we might take for granted nowadays, which is the fact that it is set in the Victorian era it was originally written in, rather than the time it was released in.

Another factor that sets The Hound of the Baskervilles aside from other contemporaries is that, as well as a detective story, it is a wonderfully spooky Gothic tale, with a crumbling mansion, a seemingly supernatural beast and fog shrouded moors, all of which translate perfectly to the screen, with an ambience reminiscent of the classic Universal horror films. It is perhaps not surprising that Hammer chose this same tale to follow up their Dracula and Frankenstein films.

Of course, a detective story is only as good as the detective and thankfully we have one of the best portrayals of Holmes ever. Rathbone is a dead ringer for the Holmes depicted in the Sidney Paget illustrations that accompanied the original publication, but he also brings a steely determination and energy to the part, and makes such an impact that it is easy to forget that the character is absent from most of the middle third of the story.

Nigel Bruce's take on Watson has come in for some stick over the years and there is no denying that this is a far more buffoonish than the book version. However, in his defence, Watson does have to be slightly behind events so that Holmes has someone to explain things to for the benefit of the audience, and in addition, there is no shortage of the other essential traits we associate with the character, the tenacity and loyalty.

Rounding out the films credentials as a work of horror is the supporting cast of suspicious characters, featuring no less than John Carradine as the Baskerville butler, a man who could read a shopping list and make it sound like a sinister threat, and Lionel Attwill as Dr Mortimer, the man who brings the whole matter to Holmes in the first place for reasons that seem unclear. Attwill usually gets typecast as sinister or sleazy villains and it is not surprising that he would go on to play Holmes nemesis Professor Moriarty in the later Rathbone film Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon.

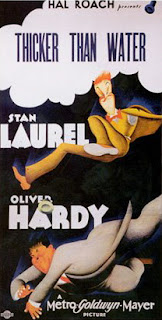

Making less of an impression is Sir Henry Baskerville himself, played by future TV Robin of Sherwood Richard Greene, although perhaps that is more a case of being overshadowed by the charisma and talent of the rest of the cast. In a sign perhaps of how little 20th Century Fox anticipated the success of the film, and the chances of any sequels, Greene actually gets star billing on the poster, over Rathbone and Bruce, despite this only being his second movie outing.

All of this is helped by a script that sticks to the basic storyline and zips along a good pace, intriguing without being confusing, while still leaving time to learn about something of the character of Holmes and soak up the glorious gloomy atmosphere of Grimpen Mire.