One Good Turn sees Stan and Olly down on their luck, jobless, penniless, with no more possessions than the shirts on their backs and the car they live in. They are, as they put it, “victims of the Depression”, but when a kindly lady offers them a meal, a misunderstanding leads to the pair trying to repay her kindness. However, this being a Laurel and Hardy film, things do not go to plan, and once again we see the truth of the old adage that “no good deed goes unpunished”.

One Good Turn has all of the elements of a solid Laurel and Hardy talkie film. We get Stan's well-meaning stupidity (setting fire to their tent and put it out one cup of water at a time), Olly turning on the Southern charm to get them fed, bickering and friendship between the two, their arch nemesis James Finlayson, escalating tit for tat slapstick (this time at the dinner table) and damage of other people's property.

It is this final element that gives One Good Turn a destructive and slightly jarring (albeit memorable) climax, as mild mannered Stan turns on Olly, after a barrage of wrong accusations as to his integrity. The red mist descends to the extent that Stan takes an axe to the woodshed of their hosts, while Olly cowers inside.

One Good Turn(B&W) 1931 - Laurel & Hardy by herbert-hueller

Horror and Sci-Fi films old and new, weirdo trash, arthouse, forgotten gems, well loved classics, and I'm watching the original Dr Who from the beginning.

Sunday, 29 November 2015

Monday, 16 November 2015

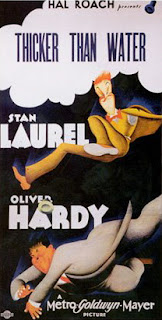

Thicker Than Water (1935)

The final short to star Laurel and Hardy together, Thicker than Water sees the usual formula of domestic bliss turning to domestic chaos, with brilliant slapstick, a dash of Stan’s wordplay (“Is Mr Hardy Home?” “Yes but he’s not in”) and surrealism.

The story opens at the home of Mr and Mrs Hardy, and their lodger, a certain Mr Laurel. The two men want to go out to watch the ball game – but the lady of the house (played by the diminutive Daphne Pollard) will not hear of it, at least until they have done the washing up. The sight of the under five feet tall Pollard browbeating the hapless duo is mined to great comic effect, and the washing up goes as smoothly as might be expected, especially for those who have seen Helpmates.

The rest of the story revolves around money and debt, in particular, the debt owed to furniture store owner James Finlayson, and the money that Olly gave to Stan to cover this month's payment, money that, needless to say, did not get to where it should have, leading to further ear bending and emasculation for Olly.

In an effort to regain some of his crushed male pride, he is persuaded by Stan to withdraw the couple’s remaining bank balance in order to buy furniture outright, so they are not in hock to Finlayson. As we seen time after time in the world of Laurel and Hardy, no good deed goes unpunished, and Olly’s chivalrous attempts to help a lady get a Grandfather clock at an auction leave him minus his cash and holding the timepiece. Mrs Hardy does not approve, and registers her disapproval, with the help of a frying pan, on Olly's head, requiring a trip to the hospital and a surreal twist ending.

Surrealism is perhaps one of the more underappreciated elements of Laurel and Hardy films, and it crops up here in two distinct ways. Firstly the body swap gag, where, after a blood transfusion required by Mrs Hardy taking a frying pan to Mr Hardy, Olly dresses, talks and acts like Stan, and vice versa. The voices are dubbed but the pair do an uncannily excellent job of mimicking each other’s body language and tics of each other. These sort of jarringly odd punchlines did crop up from time to time, such as Stan’s grotesquely distended belly at the end of Below Zero

Secondly is the recurring gag where by the pair change to the next scene by having one of them drag the frame in from off-camera, a clever way of getting quickly from one scene to another, seemingly quite innovative for the time.

Laurel And Hardy - THICKER THAN WATER - 1935 by nostalgia04

Sunday, 8 November 2015

Should Married Men Go Home? (1928)

While never rising to the heights of some of their other silent films, Should Married Men Go Home? is an enjoyable and amusing Laurel and Hardy short

The story comes in two distinct halves, starting with a scene of domestic bliss at the home of Mr and Mrs Hardy, bliss that is soon destroyed by the appearance on the doorstep of Stan Laurel, intent on dragging his friend out for a game of golf. When attempts to avoid him fail, Stan is invited in (through gritted teeth) where he proceeds to cause destructive chaos. When Mrs Hardy packs them both off to the gold course, the pair meet up with a couple of lady golfers, as well as Stan’s oversized hat, a mud-bath, and a toupee that just will not stay in place.

The film is an important milestone in the Laurel and Hardy story, as this is the first time they are billed together as a duo. The performers and film-makers are still finding their feet in terms of pacing and execution of the gags, although it is interesting to see that some of them use film editing, something that helped the pair develop from their theatrical roots to being movie comedians. The characters are still being formed, lacking their hats and tatty suits, and the dynamic of their relationship is subtly different, still being friends, but the idea of Olly wanting to avoid Stan and spend time with his wife would not last.

A couple of the routines would crop up later in talkie films, with Olly's bungled attempts to avoid Stan at home getting a second outing in Come Clean, while Stan's constant undermining of Olly's attempts to preserve their meagre cash reserves at the drug store would be reworked in Men O'War. The latter in particular worked much better with dialogue.

There's plenty of slapstick too, from a piece of turf mistaken for a wig to Olly's disastrous attempt to jump over his picket fence, to the messy anarchic ending, something that would crop up repeatedly in their films. In Battle of the Century it was pies, in You're Darn Tootin' it was pants, here the film ends in a mud bath, as once again Laurel and Hardy cause inadvertent but hilarious chaos wherever they go.

Wednesday, 4 November 2015

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947)

Very loosely based on the classic James Thurber short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is a fun little romp, with a refreshingly dark and unsentimental side that makes it stand apart from other comedies of the era.

Danny Kaye plays the title character, a young man working at a New York publishing company, somebody with no greater life plans than getting to the end of the day without falling foul of his bullying boss, insufferably bossy mother, and immature and irritating fiancé. The only escape for poor Mitty is his own private fantasyland, where, whether as a brilliant surgeon, a dashing fighter pilot, or a sure shot cowboy, he is always the hero. However, fantasy and reality start to merge when, back in the real world, a beautiful woman drags Mitty into a plot involving stolen jewels – a beautiful woman who happens to look exactly like a woman from his dreams.

The film works best during the fantasy sequences, with the production design in the individual dreams both detailed and surreal (and in the hospital sequence, weird, almost like Cronenberg's Dead Ringers). Director Norman McLeod plays up this visual element more than in some of his previous work with the likes of the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields, where the emphasis was more on surreal sight gags and word play.

There is also no attempt to gloss over how grim much of Mitty's life is, being undervalued at work and home, henpecked and demeaned by the men and women in his life. Things get genuinely dark too, when those around him convince Mitty that his active imagination is in fact a serious mental illness, and send him to see a shrink, played by, of all people, Boris Karloff. Again, credit to McLeod for balancing the light and dark of the film, ultimately making Mitty a sympathetic rather than just pathetic character.

Monday, 2 November 2015

The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985)

The author Shirley Jackson once wrote, “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality”, and such thinking may go some way to explain the appeal of watching films with a fantasy or escapist element to them. Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo is a clever and charming exploration of this idea, as well as our relationship with movies, movie characters, and the people who bring them to life. Although the film is a move away from the more usual explorations of contemporary New York, it still has plenty of his familiar tropes, as well as a surprising twist in the tail.

Cecilia (Mia Farrow) lives in Depression era New Jersey, struggling to get by on her waitress wages. Her husband, Monk (Danny Aiello) is no help, spending his days playing pitch and toss with his unemployed friends, and his nights drinking, gambling and occasionally hitting Cecilia. Her only escape is the movie theatre, losing herself week after week in the fluff and glamour on the silver screen. During one viewing of her latest favourite, The Purple Rose of Cairo, the impossible happens – her favourite character, Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) comes out of the screen into reality – and declares his love for her. This has serious implications for her marriage – but also for the rest of the characters trapped on screen, who can't move the story forward without their leading man.

The film within a film, The Purple Rose of Cairo is brilliant, a perfect pastiche of the bright and breezy RKO fluff musicals with their mix of beautiful people flitting between big apartments and New York nightclubs, with singers, big bands, and endless champagne. When Baxter steps down into the audience, this takes the film into the world of magical realism described by the writer Matthew Strecher as “what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe”. While atypical of Allen's work overall, it is an area he does move into from time to time, in films such as Play It Again Sam and Midnight in Paris. In addition, as with those films, Allen never explains the cause of the fantastic events, leaving them open to interpretation – is it in people's imagination, some sort of mass hallucination – or has the sheer willpower of a devoted movie fan bought her idol to life?

The characters themselves are a little two dimensional, but in the context of the era, the films Cecilia likes to watch, and the fantastic events depicted, the slightly unnatural sounding dialogue, such as the onscreen characters having a philosophical discussion, does not seem as jarring as it would in a contemporary setting. Farrow helps, bringing a likeable charm to her character, and her sometimes neurotic mannerisms make her the nearest we have to the “Woody Allen” character that usually crops up if the man himself does not in one of his films.

The period detail feels convincing, and the film clearly had some money spent on it, but more importantly, Allen clearly also spent time on the script, and as feels engaged in the subject, so we feel engaged too. The Purple Rose of Cairo is a film about films, one which looks into not just the creative process that lies behind them, but also the relationship between the filmmakers, the fictional characters they create, and the audience who fall in love with them. Here Allen ask questions as to what it really is that we fall in love with – the actor, the character they are playing, or the image we have of them.

The crux of the drama and comedy is the clash between the world of the movies (perfection, order, repetition, happy endings) and that of real life (imperfect, real, chaotic, unhappy endings). Ultimately Allen celebrates both of these for being what they are, and while he does not appear to be favouring one over the other, he seems to suggest that "real" will eventually win out whether we like it or not. This is most evident in the heartbreaking climax, where Allen refuses to pander to the sort of happy endings of classic movie fantasy, even though he celebrates these as good things in their own world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)