Now Voyager appeared as part of the first wave of Hollywood's brief love affair with psychoanalysis, along with the likes of Hitchcock's Spellbound. This Freudian undertone sets it apart from standard Hollywood romantic melodramas, and the plot of a person forced to repress their true personality by an overbearing family figure seems to have struck a chord with gay film fans, amongst whom it has a fanbase to this day.

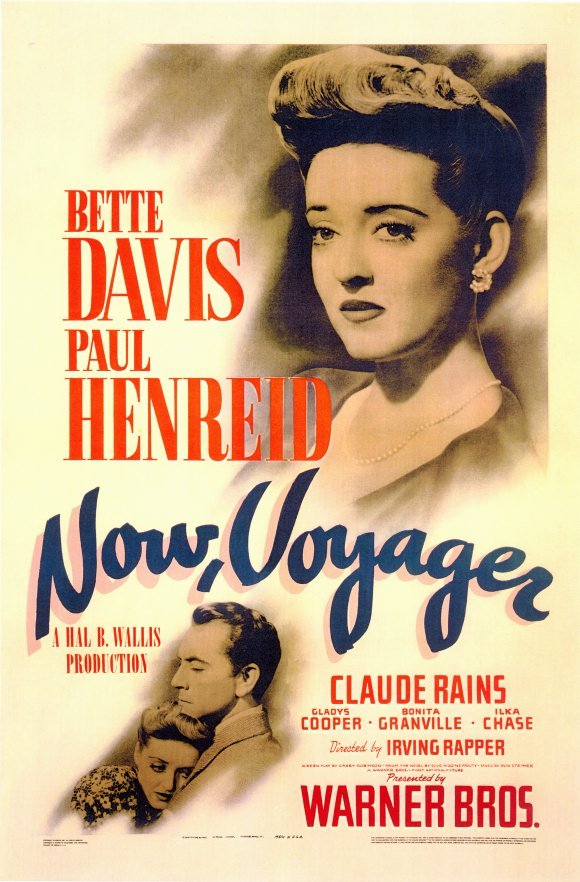

Bette Davis plays Boston heiress Charlotte Vale, a neurotic mess, largely due to her domineering mother (Gladys Cooper). After coming under the care of psychiatrist Dr. Jasquith (Claude Rains), Charlotte reinvents herself, going from frumpy introvert to glamorous woman about town. While on a cruise she meets and fall in love with a married man, Jerry (Paul Henreid). How will her mother react to the newly independent Charlotte? And can she ever find happiness with Jerry?

Drama is based around conflict and there is no shortage of that in this film, with Charlotte clashing with her mother, Charlotte's sister clashing with her mother, her mother clashing with Dr Jasquith, and Charlotte clashing with her feelings for Jerry. What makes the drama seem so fresh is the liberal attitude of Jasquith. He is more interested in Charlotte being happy, rather than have her conform to the stuffy morality of her background, or, indeed, of the wider society of the day, something that makes the appeal to the film's gay fanbase obvious. In addition, the script goes against the grain of contemporary romantic films by not going for an obvious path to true love, and seeming to accept that relationships are often complicated and happiness not always conventional.

There is plenty of fun to be had watching Bette Davis playing against type as the monobrowed dowdy Charlotte we see at the beginning of the film, emerging from her chrysalis into the polar opposite, glamorous, adventurous, and fun loving, not giving a damn for the stifling world of upper middle class Boston and the sense of duty and obligation that comes with it.

Film and psychoanalysis are the around the same age, as the Lumiere brothers started screenings of moving pictures in 1895, the same year that Freud published Studies in Hysteria, his first foray into what would become psychoanalysis. If anything it is the depiction of psychoanalysis itself, or at least the Hollywood version of Freud's work that dates Now Voyager. It portrays the mystery of the human psyche as being like a whodunnit, one that can be unravelled with the aid of the right clues, an approach that now seems a little unsophisticated.

No comments:

Post a Comment